Confessions of an English Teacher

I am not English but I use English to be me.

‘English bolu bolu tond dukhta maajha’

‘When I speak English for too long, my mouth hurts,’ my five-year-old nephew declared.

We had been delighted when he started speaking in English. English is not our first language. Not even our second. We speak in Marathi, Hindi, and a mix of Marathi and Hindi, before we reach for English.

When my nephew started playing with English, we loved the way he rolled words like ‘Jupiter’ and ‘Spiderman’. Speaking in English was getting him more attention. So he used it non-stop. Two days later, we were surprised to hear his protest against speaking in English. His mouth hurt.

How English Hurts Us

When my nephew was even younger, I did a course called Teaching English to Speakers of Indian Languages from Delhi. I became an English teacher, an identity that felt like a loose but pretty hat. It kept slipping, but I delighted in wearing it.

Later, I moved to Bengaluru. I worked as an English teacher at a non-profit scholarship program for students from low-income backgrounds. Since I couldn’t speak the local language of Kannada, I would end up speaking in English all the time. With students and colleagues, friends and strangers. It was exhausting. My mouth had begun to hurt, just like my nephew’s.

It reminded me of a harrowing week in my childhood, when our class teacher punished us with 26 sit-ups for speaking even one word outside English. Even ‘Arey’ and ‘Abbe’ were counted by the English monitors. Thankfully, the teacher did not persist with this linguistic fascism. Our urge to chat in Hindi was too wild to tame.

As an adult, I read and wrote mostly in English. I thought I was comfortable with it. But when it became the only language in my mouth, I felt like spitting it out. While I savoured poems and essays in English, I needed my languages for banter. For comic relief. It felt hard to help and ask for help in English. So i didn’t.

One morning, in the Zoom class, I confessed to my students, ‘I know I am your English teacher but I must tell you this. I don’t like English.’ Shocked face emojis popped on their windows.

‘I love you guys more than I love English,’ I added. The emojis turned into red hearts. I didn’t want them to serve English. I wanted English to serve them. I explained: ‘I hate that English is used to put people down. But that’s exactly why I teach it. So that you never have to feel suppressed by the anxiety and shame of not knowing English’

I wish the language that dominated the world was easier to read and gentler to the mouth. I wish every rule did not have twenty exceptions and the spellings did not leave us with googly eyes and the pronunciation did not give away caste and class.

English has to calm down with its perfect tenses and modal verbs. The silent letters can go and chill in another room if they don’t want to be pronounced! I get it though. I feel like a big silent letter myself. In many gatherings where English, fancy coffee, and money flow but not ease, not a sense of being at home.

English has to calm down

Not everything needs to be translated to English. I need to use rawa, not semolina, tawa not skillet, thelaa not barrow, tapri not stall. We love bad poetry because it sounds posh. We trust scamster Godmen just because they speak in English. We equate English to wisdom. Could there be a stranger assumption?

I have been privileged enough to have access to English. I am a second generation English learner. But I am sensitive to how some of my closest family members, friends, and even my favourite celebrities have had a history of embarrassment and fear around English.

As a child, I was mocked in class because I read chaos as chaa-aws. The History teacher did nothing to stop the kids who laughed. The best English teacher in our school couldn’t believe that I wrote a poem in English. If it were not for the next two English teachers and their encouragement, I wouldn’t have any relationship with English.

Eventually, I left Bengaluru. My mouthfeel improved when I could use Marathi and Hindi. Instead of teaching English, I could teach writing and creativity. I found

where we smoothly switched between languages and creative forms.Does it makes sense to bitch about English in English? It absolutely does. That’s why I love English too. She connects me with people from my country, continent, and all those places where English is spoken and gleefully broken. We can bitch about her together. We can create spaces for the likes of us, multilingual creatives.

English as a Tool, Not an Identity

Chandrika, my mentor at the non-profit organisation, would praise English precisely because it is a distant language. It helps us see ourselves from a distance. Our mother tongue and our native languages are too close to our sense of self. We need a distant language to access our independent identities.

I realised how English helped me outline my own identity. Growing up, it gave me a space to express myself, and to think whole new thoughts that were unnecessary or taboo in my languages. Everything from philosophy to sexuality felt safer and easier to discuss in English. Creativity, art, pedagogy, body, world cinema, haiku - so many things that make me who I am today - are brought to me by the river of English.

What Chandrika said deeply resonated with me. It made English sound like a fancy new camera lens that helps me shoot photographs in a whole new way. And it is precisely that. English is a technology for me. Not an identity. Just like I am not my laptop or phone, even though I use them constantly, I am not English.

I am a deeply multilingual human being. I watch Iranian cinema and sing Tamil songs and Marathi patiently hides under my tongue, ready to leap out any time.

Embracing English on our Own Terms

‘It is not the English language that hurts me, but what the oppressors do with it.’ - bell hooks.

We know what the oppressors do with the English language. What can WE do with it? Can we use it without bowing down to it? Can we use it to include, not exclude?

We make English richer when we add our words to it. We make music with English when we let our accents be. We can rinse our mouths with our languages whenever English leaves us feeling parched.

You know how can use something a bit carelessly if it’s not yours? That’s why I love writing in English. That irreverence helps me be a better poet. A calmer English teacher. I am not English, but I use English to be me.

What is your equation with English?

URDU se DOSTI, a beginner's workshop facilitated by Vimal Chitra

Urdu is a language of love, history, and poetry. Discover the jaadu of Urdu with poet, screenwriter and spoken word artist, Vimal Chitra in our 2 day workshop, Urdu Se Dosti

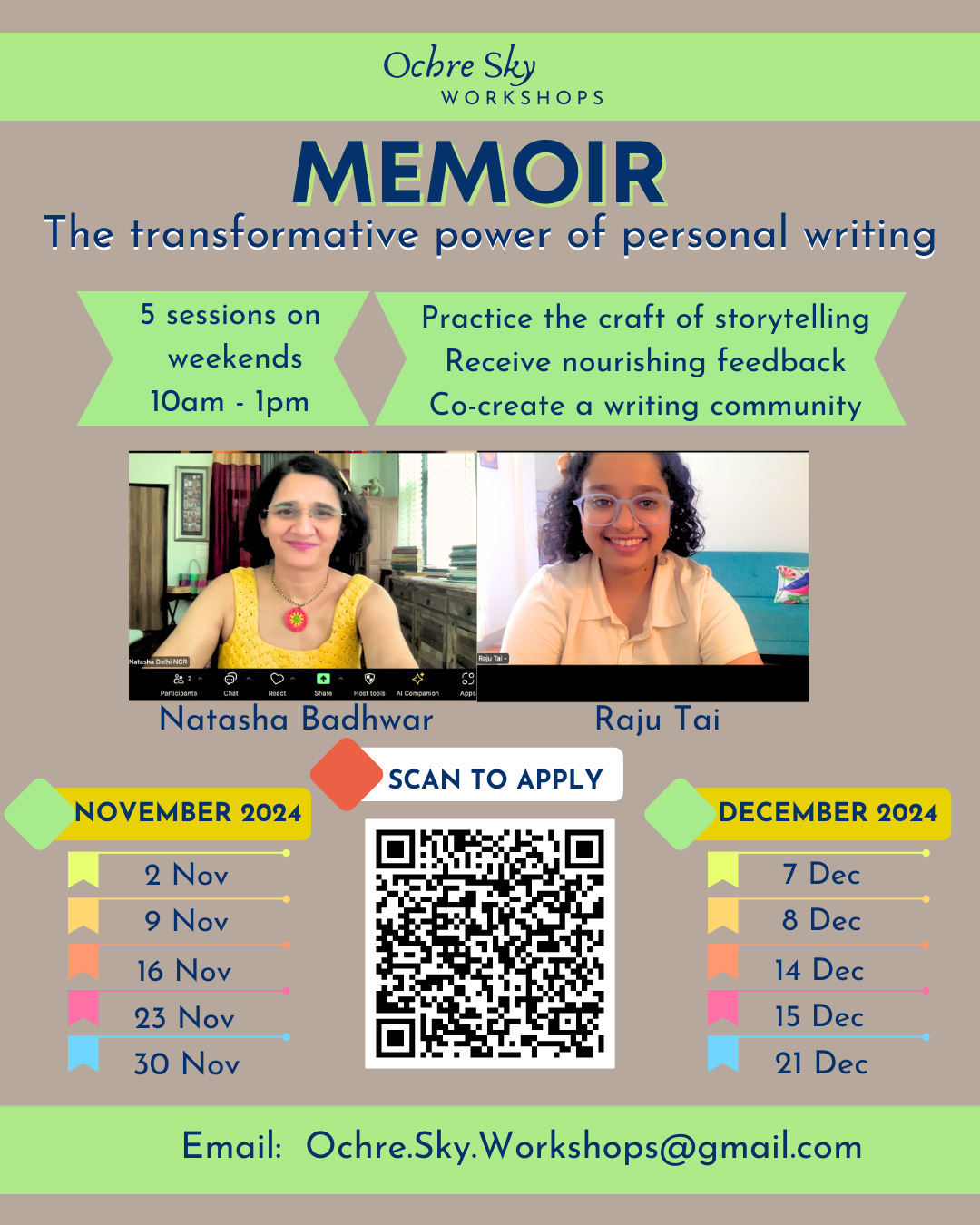

Discover the transformative power of personal writing with Natasha Badhwar

and Raju Tai at Ochre Sky Stories Memoir Workshop.

Raju, if this was written in a book, I would underline so many sentences! But because I am reading this on my phone, I am noting my favourite quotes (so many!) in my journal. You spoke for so many of us, Raju. I think your essay should be read in schools so that every child feels gently held as they navigate the conflicting feelings that learning and speaking English brings. Lots of love ❤️

This is everything. As someone limited to only English, I marvel at the acrobatics, fireworks, and dance of your writing, in the only language I can understand it. But through your writing in English, I get a glimmer of those other parts of the linguistic you, and am richer for it. I am so grateful for you, and this piece, and your generosity in describing your experience. My language is flat compared to yours, but my heart wants you to know that it is not.

When I was ten, my parents took us to a different denomination of church. And like many converts, even though it was not as much of a leap as a new language, they were all in. We were all in. And it became a big part of our identity. I don’t practice now for many reasons, but the music that was a big part of me then is still my own. It makes me weep to hear it and sing it, and I cannot give the words any conviction, but the music is me and I am it, despite that. Thanks for helping me understand, and love it that way. And myself but more too.